Business pressure is growing on the UK to reach a deal with the EU on Brexit. From farmers to manufacturers, healthcare companies to banks and financial companies and SMEs to the behemoths of the CBI, the clamour is growing for the UK government to avoid a “no deal” outcome. All this is unfolding against the background of a sluggish performance by the UK economy and concerns over the lack of economic momentum –much of this blamed on the uncertainty caused by the relentless, debilitating lack of progress in securing a withdrawal deal.

Now Chancellor Philip Hammond has further racked up the pressure by repeating the findings of the Treasury’s provisional Brexit analysis earlier this year that a no-deal Brexit could mean a 7.7 per cent hit to GDP over the next 15 years, compared with the “status quo baseline”. He said that under a no-deal scenario chemicals, food and drink, clothing, manufacturing, cars and retail would be the sectors “most affected negatively in the long run”.

Let’s set aside the row over whether this is just a Remain-supporting chancellor regurgitating the earlier warnings of “Project Fear” which failed to materialise. We have much to be concerned about. And it adds to the sense that Michel Barnier and the European Commission negotiating team have nothing to lose by holding out and pushing the UK to the brink – and beyond. But we should also look more closely at what is at stake within the EU itself. For Brussels is under equal and equivalent pressure to agree a withdrawal deal.

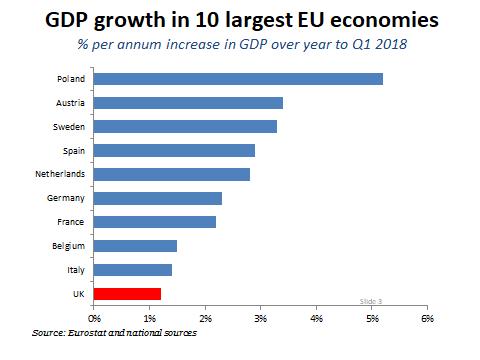

The Eurozone economies, too, need to secure an agreement that minimises disruption to continental trade with the UK and wider negative effects. It’s generally assumed that the UK is the economic laggard, and that the EU, underpinned by the Single Market and the customs union, is enjoying a superior rate of economic growth and rising exports. But the latest figures suggest otherwise.

Eurozone economic growth slowed further in the second quarter of this year. Eurostat estimates that gross domestic product in the 19 countries sharing the euro, far from growing faster than the UK, is trailing our performance. It is grew by 0.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter in the April-June period, not only below analysts’ expectations but also slightly behind the 0.4 per cent growth recorded for the UK over this period.

The UK’s improvement on the first three months of the year has been attributed to the spell of warmer weather – though the Eurozone countries also enjoyed more clement conditions after the freeze of the opening months. Bert Colijn, a senior economist at ING Bank, said: “Trade uncertainty seems to have already had a significant effect on the Eurozone economy in Q2…

With lower confidence among businesses and consumers, concerns have likely translated into somewhat weaker domestic demand growth. In an economy in which capacity constraints abound and credit conditions remain favourable, confidence is the likely factor keeping investment down.” The Eurozone’s second quarter slowdown follows a sharp deceleration in the first three months of the year.

The combination of a slower global recovery and strong euro caused exports to plunge in the three months to March, with GDP growth falling from 0.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2107 to 0.4 per cent. Industrial production shrank in April and economic sentiment fell throughout the quarter. A stronger euro has taken a bite out of export growth, while rising inflation has been weighing on household spending – all too familiar here.

The euro area is also having to contend with political uncertainties – a fragile populist coalition in Italy, continuing turbulence in Spain, evidence of growing disenchantment with President Emmanuel Macron in France, while in Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel has been under pressure from her coalition partners. Meanwhile, tensions with the United States, the Eurozone’s largest trading partner, are high following tit-for-tat tariffs implemented in June.

According to FocusEconomics, five Euro economies, including major players France and Germany, have had their growth prospects cut. Cyprus, Estonia, Greece and Luxembourg were the only economies to see higher GDP growth forecasts, while Belgium, France and Italy will be the slowest growing – all expanding below two per cent. Germany is forecast to grow by 2.1 per cent this year.

Latest data from France suggests the economy expanded modestly in the second quarter, while industrial production contracted for the third consecutive month in May – the fourth monthly decline so far this year. In addition, consumer confidence dropped to a near two-year low in June amid mounting unemployment fears. Consumers are growing more fearful that the economic recovery is running out of steam.

In Italy recent industrial output figures in April and May, and the average of PMI readings throughout the quarter point to a slowdown. Consumer spending also seems to have cooled, as retail sales contracted heavily in April and rebounded timidly the following month. If, as seems likely, world trade continues to slow as US tariffs continue to bite and President Donald Trump threatens more, the Eurozone’s leading companies will be anxious not to have their prospects further damaged by a “no deal” UK exit with all that this means for companies exporting to the UK.

Exports from the EU to the UK totalled £341 billion last year, with a surplus vis-à-vis the UK of £67bn. While the UK enjoyed a £28bn surplus on trade in services, this was outweighed by a deficit of £95bn in goods. Two EU export sectors look particularly exposed: cars and food products. German car makers have long warned that Brexit would hit their exports to Britain and disrupt international supply chains.

About a fifth of all cars produced in Germany are exported to the UK, making it the single biggest destination by volume. As for food and non-alcoholic drink imports from the EU, these are running at £24bn a year – trade which EU suppliers will be acutely anxious to protect. As the clock ticks on, I see intensifying pressure from business on both sides for a deal to be reached – and preferably with the minimum of delay.

Source: Scotsman