A housing charity has called for the Government to spend £214 billion on creating three million new homes to solve the social housing crisis.

In the wake of the Grenfell disaster, Shelter brought together 16 independent commissioners from across the political spectrum to write a report on the issue.

Entitled Building For Our Future: A Vision For Social Housing, it urges ministers to invest in a major 20-year housebuilding programme and massively extend the criteria for who is applicable for social housing.

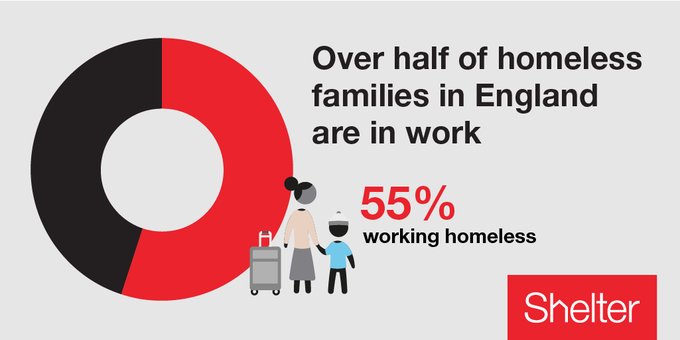

The report recommends building 1.27 million homes for “those in greatest housing need”, including homeless households, the disabled and long-term ill, or those living in very poor conditions.

It also wants the Government to create 1.17 million homes for what it calls “trapped renters”, younger families unable to get on the housing ladder, as well as 690,000 homes for older private renters who face housing insecurity beyond retirement.

The authors of the report, who include former Labour leader Ed Miliband, ex-Tory chairman Baroness Warsi, Baroness Lawrence, mother of murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence, TV architect George Clarke and Grenfell survivor Ed Daffarn, spent a year speaking to hundreds of social tenants, more than 30,000 members of the public as well as housing experts.

Their findings suggest it would require an average yearly investment of £10.7 billion to pay for the new homes, but analysis by economic experts suggests up to two-thirds of this could be recouped through “housing benefit savings and increased tax revenue each year”.

The charity said that, on this basis, the true net additional cost to the Government would be about £3.8 billion on average per year over the 20-year period.

Baroness Warsi said: “Social mobility has been decimated by decades of political failure to address our worsening housing crisis.

“Our vision for social housing presents a vital political opportunity to reverse this decay. It offers the chance of a stable home to millions of people, providing much needed security and a step up for young families trying to get on in life and save for their future.”

Mr Miliband said: “The time for the Government to act is now. We have never felt so divided as a nation, but building social homes is priority for people right across our country.

“This is a moment for political boldness on social housing investment that we have not seen for a generation.

“It is the way to restore hope, build strong communities, and fix the broken housing market so that we meet both the needs and the aspirations of millions of people.”

Other suggestions in the report, which will be presented to Prime Minister Theresa May and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn on Tuesday, include creating an Ofsted-style consumer regulator to protect residents in social housing and private renting, a new national tenants’ voice organisation and improved national standards in maintaining publicly-owned homes.

Communities Secretary James Brokenshire said: “Providing quality and fair social housing is a priority for this Government and our Social Housing Green Paper seeks to ensure it can both support social mobility and be a stable base that supports people when they need it.”

He added: “Our ambitious £9 billion affordable homes programme will deliver 250,000 homes by 2022, including homes for social rent. A further £2 billion of long-term funding has already been committed beyond that as part of a 10-year home-building programme through to 2028.

“We’re also giving councils extra freedom to build the social homes their communities need and expect.”

Source: Shropshire Star